Arrow Functions in Class Properties Might Not Be As Great As We Think

Disclaimer: This article was written in 2017 and may not be representative of the current state of technologies.

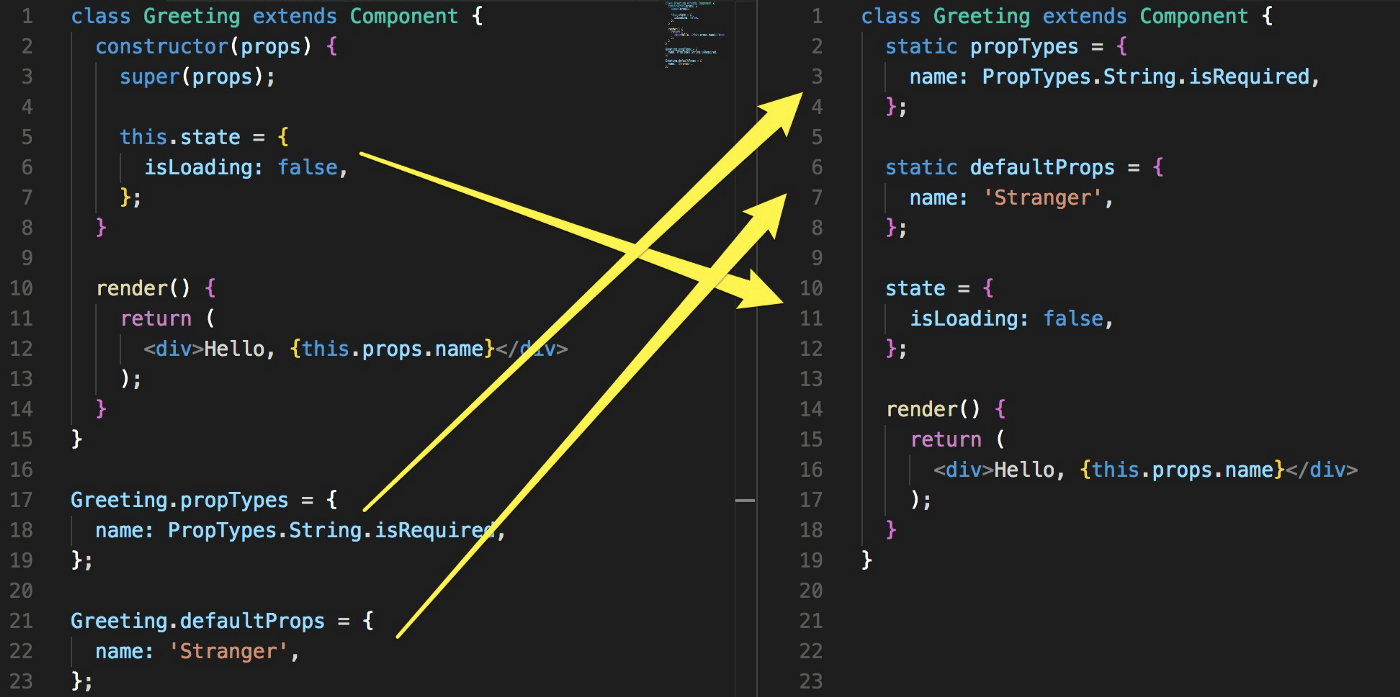

Since the last year, the Class Properties Proposal simplify our life, especially in React with the internal state , or even with statics ones like propTypes and defaultProps.

Furthermore, Class Properties/Property Initializers seems to be more trending in the last six months to handle binding in React instead of a bind call in the constructor.

https://twitter.com/housecor/status/921841848641097728

class ComponentA extends Component {

handleClick = () => {

// ...

};

render() {

// ...

}

}

Arrow functions in class field properties seem useful because they’re autobind, in short, no need to add this.handleClick = this.handleClick.bind(this) in the constructor.

But, should we really use arrow functions in class field properties?

First of all, let’s see what class properties do under the hood.

What Class Properties look like once transpiled to ES2017

Let’s code a simple class with a static property, an instance one, an arrow function in property, and a usual function as method with the plugin transform-class-properties.

class A {

static color = 'red';

counter = 0;

handleClick = () => {

this.counter++;

};

handleLongClick() {

this.counter++;

}

}

Once we go to the Babel REPL to get this class transpiled to ES2017 with the following presets: es2017 and stage-2.

We got this transpiled version:

class A {

constructor() {

this.counter = 0;

this.handleClick = () => {

this.counter++;

};

}

handleLongClick() {

this.counter++;

}

}

A.color = 'red';

As we can see, instance properties have been moved inside the constructor and the static one moved to an afterward declaration.

Personally, I like the addition of static keyword as we can now directly export a class with static properties.

On instance properties, it’s great too, because in our code (not transpiled one) the constructor will be less bloated with declarations.

For our arrow function in a property, handleClick got moved in the constructor too, such as an instance property.

For our usual function method handleLongClick, nothing change.

Property initializers may be useful for properties, but when it comes to arrow functions in class properties, it feel like a hackish way of achieving a binding.

Did you spot some issues? Let’s see what I found.

Mockability

If you want to mock or spy on a class method, the easiest and proper way to do so is with the prototype as all changes to the Object prototype object are seen by all objects through prototype chaining.

Let’s say we want to do some tests with our previous class A.

class A {

static color = 'red';

counter = 0;

handleClick = () => {

this.counter++;

};

handleLongClick() {

this.counter++;

}

}

A.prototype.handleLongClick is defined.

A.prototype.handleClick is not a function.

Oops, since we used an arrow function in a class property our function handleClick is only defined on the initialization by the constructor and not in the prototype. So, even if we mock our function in the instantiated object, the changes won’t be seen by other objects through prototype chaining.

Inheritance

Let’s define our base class A.

class A {

handleClick = () => {

console.log('A.handleClick');

};

handleLongClick() {

console.log('A.handleLongClick');

}

}

console.log(A.prototype);

// {constructor: ƒ, handleLongClick: ƒ}

new A().handleClick();

// A.handleClick

new A().handleLongClick();

// A.handleLongClick

If class B inherit from class A ,handleClick won’t be in the prototype and we can’t call super.handleClick from our arrow function handleClick.

class B extends A {

handleClick = () => {

super.handleClick();

console.log('B.handleClick');

};

handleLongClick() {

super.handleLongClick();

console.log('B.handleLongClick');

}

}

console.log(B.prototype);

// A {constructor: ƒ, handleLongClick: ƒ}

console.log(B.prototype.__proto__);

// {constructor: ƒ, handleLongClick: ƒ}

new B().handleClick();

// Uncaught TypeError: (intermediate value).handleClick is not a function

new B().handleLongClick();

// A.handleLongClick

// B.handleLongClick

If class C inherit of class A, but implement handleClick as a function instead of an arrow function, handleClick will only executes super.handleClick() and nothing else. Strange isn’t?

It’s because the instantiation of handleClick in the constructor of our parent class overrides it.

C.prototype.handleClick() will call our implementation but will fail with the previous error: Uncaught TypeError: (intermediate value).handleClick is not a function.

class C extends A {

handleClick() {

super.handleClick();

console.log('C.handleClick');

}

}

console.log(C.prototype);

// A {constructor: ƒ, handleClick: ƒ}

console.log(C.prototype.__proto__);

// {constructor: ƒ, handleLongClick: ƒ}

new C().handleClick();

// A.handleClick

If class D is a plain class that inherit from class A, he will have an empty prototype and new D().handleClick() will log A.handleClick.

class D extends A {}

console.log(D.prototype);

// A {constructor: ƒ}

console.log(D.prototype.__proto__);

// {constructor: ƒ, handleLongClick: ƒ}

new D().handleClick();

// A.handleClick

Performance

Now the interesting part, let’s talk about performance.

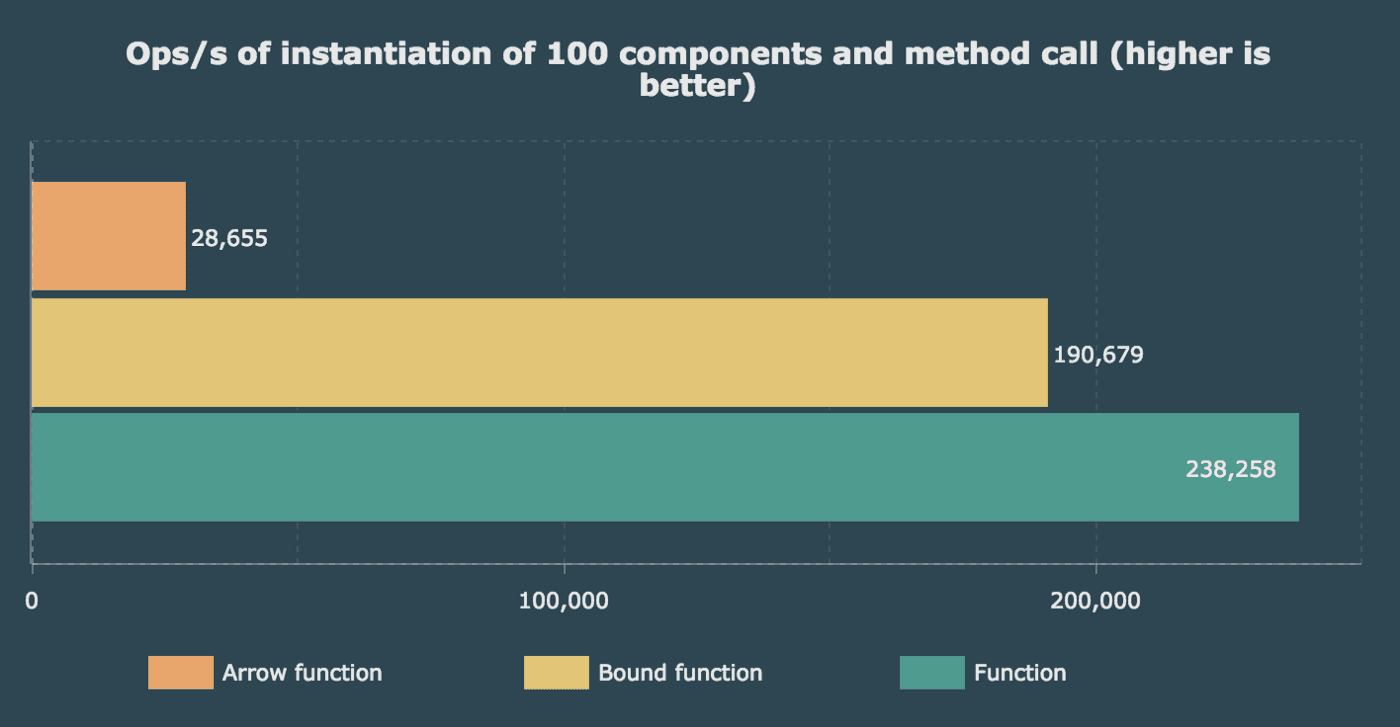

We know that usual functions are defined in the prototype and will be shared across all instances. If we have a list of N components, these components will share the same method. So, if our components get clicked we still call our method N times, but it will call the same prototype. As we’re calling the same method multiple times across the prototype, the JavaScript engine can optimize it.

On the other hand, for the arrow functions in class properties, if we’re creating N components, these N components will also create N functions. Remember what we’ve seen in the transpiled version, class properties are initialized in the constructor. Which means if we click on N components, N different functions will be called.

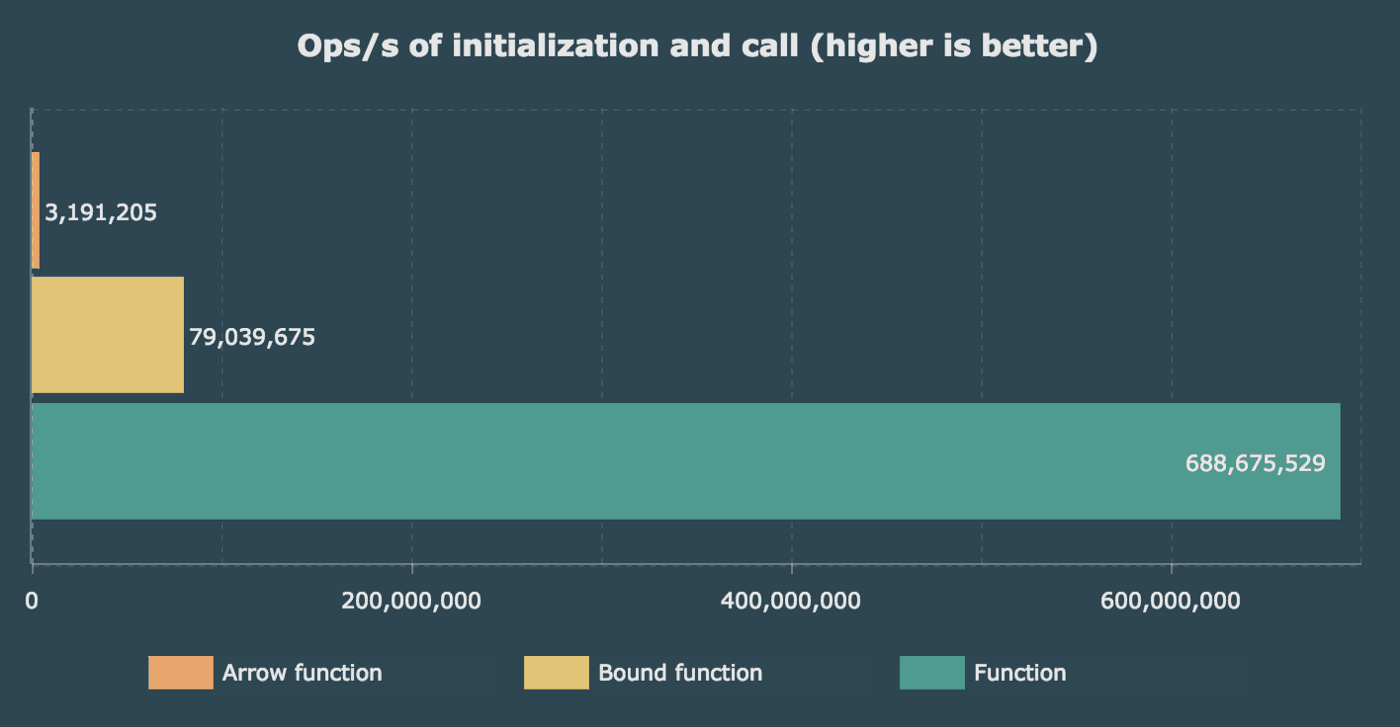

Let’s see how they are doing in a benchmark with V8 engine (Chrome).

The first one is simple, we only measure the instantiation time, and we call our method one time.

Beware that number doesn’t really matter in this one, since one instantiation won’t be noticed in your application and we’re talking about operations per second and the number are high enough. I’m more concerned by the gap between our functions.

For the second one, I used a representative use case. The instantiation of 100 components — like a list — which after we called the method one time on each.

All benchmarks were run on a MacBook Pro 13" 2016 2GHz on Mac OS X 10.13.1 and Chrome 62.0.3202.

In short, to improve performance, you should declare your shared method in the prototype and only bound it to the context if you need to (if you pass it as prop or callback). It makes sense to bound our shared methods to the prototype and initialized our properties in the constructor of each instance, but methods not much.

We’re still talking about high ops/s, but we clearly see that arrow functions in class properties are not as performant as we thought.

And yes you’re right, the usage of property initializers won’t be noticed in our applications unless we instantiate many components. Yes we can see this as a premature optimization and you’re right premature optimizations are the root of all evil — with E Corp — but instead, can we see arrow functions in class properties as premature feature or misused feature? Hopefully, engines will optimizes the arrow functions in class properties.

P.S: Class properties for properties are such a great improvement!

I’ve seen this in many application and libraries, even ones that contain components we can instantiate multiple times. Should we really use this ESnext feature for class methods in our packages knowing that can impact — for the moment — our performance?

Personally, I don’t think that arrow functions in class properties are convenient enough — in some cases — at the expense of the performance.

Our savior will be the autobind-decorator, unfortunately it’s only available with babel as it’s still a proposal at stage 2.

class Component {

constructor(value) {

this.value = value;

}

@autobind

method() {

return this.value;

}

}

Even this, they also recommend to avoid autobind on all methods or class:

It is unnecessary to do that to every function. This is just as bad as autobinding (on a class). You only need to bind functions that you pass around. e.g.

onClick={this.doSomething}. Orfetch.then(this.hanldeDone)— Dan Abramov

I was the guy who came up with autobinding in older Reacts and I’m glad to see it gone. It might save you a few keystrokes but it allocates functions that’ll never be called in 90% of cases and has noticeable performance degradation. Getting rid of autobinding is a good thing — Peter Hunt

Conclusion

The initialization of arrow functions in class properties are transpiled into the constructor.

Arrow functions in class properties won’t be in the prototype and we can’t call them with

super.

Arrow functions in class properties are much slower than bound functions, and both are much slower than usual function.

You should only bind with

.bind()or arrow function a method if you’re going to pass it around.

Knowing how arrow functions in class properties are handled under the hood and with these benchmarks, you should be able to make an informed choice and aware of the possible consequences.

What do you think? Will you still use it? How will this affect you?

Feel free to share your thoughts.